Spring cleaning had recently descended upon our basement and it was time to purge. I began with my daughter’s bin of elementary school work. As I read each worksheet and admired each drawing, I couldn’t help but remember how far we had come.

We adopted Ani from a Bulgarian orphanage when she was five years, 11 months. She weighed 23 pounds. She had never learned to chew or sip. She had never taken a bath or had her hair washed. She had never brushed her teeth. She had never been comforted, rocked or held. She didn’t know Bulgarian, but “spoke” infantile babble. She didn’t understand how to play with toys. She was a little lost soul, but one with a magnetic smile and unwavering spirit.

“Other Health Impaired Issues” Diagnosis

Upon bringing Ani home, we requested special education tests be administered. The tests confirmed what we had initially suspected – Ani was diagnosed as cognitively impaired. However, the school psychologist felt Ani did not warrant the autism label and she was given a 504 diagnosis – “other health impaired issues.”

As Ani began her academic career, her speech teacher, a neighbor of mine, gave us the best advice for supporting her new life – “Give her experiences, as many as possible. Get her in the community. Take her everywhere you go.” We followed that advice. Ani attended nearly all of her brother’s hockey and football games. She went with my husband to the liquor store and car wash; she went with me to the grocery store and Target. She went where we went.

Her teachers’ focus was helping Ani to communicate. In the bin were dozens of “completed” worksheets; often black outlines of ordinary household objects, common foods, and everyday clothing with Ani’s recognizable scrawl underneath the picture. The goal was to have Ani cut out the object or food or clothing, glue it on another sheet of paper and label it. Her teacher’s note often said that Ani grew “tired” after cutting, gluing and labeling. For a little girl who had been rocking her life away, this was a lot of physical, mental and emotional work.

Prior Knowledge

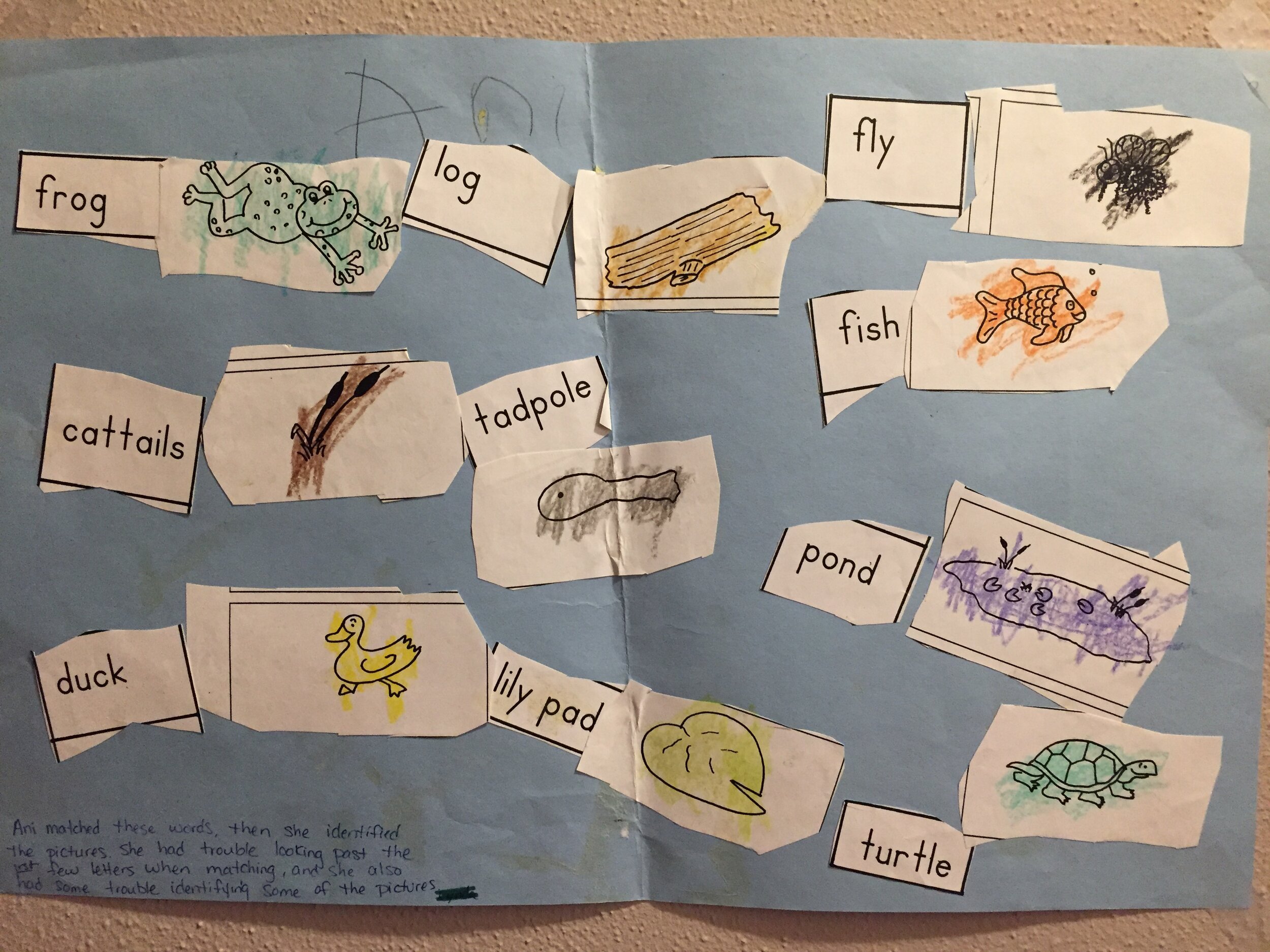

As I was sorting through the bin deciding what to keep and what to toss, I saw a green piece of construction paper with the same recognizable process – cut, glue, label. However, these pictures were much more complicated. There was a picture of a lily pad, a tadpole, and cattails, and other water-themed black outlines. The teacher’s note began, “Ani matched these these words, then she identified the pictures. She had trouble looking past the first few letters when matching, and she also had some trouble identifying some of the pictures.”

This was a second grade assignment, so Ani had been with us, in the United States, for about three years. I wondered how many typical students living in the United States their entire lives would be able to identify those items? Nearly 18 years later, I realize now how shortsighted that assignment was.

Ani had no prior knowledge of “lily pad,” “tadpole,” or “cattails.” Growing up in an orphanage severely limited her most basic experiences. In addition, we were focusing on the most essential vocabulary to help her communicate her needs and feelings.

We know the value of prior knowledge. The 1988 iconic baseball study by Recht and Leslie (1988) explained that “children with greater knowledge of baseball recalled more than did children with less knowledge” (p. 18). When Ani’s classroom teacher explained that Ani didn’t seem to understand the book they read about dogs; I agreed. We had a cat. When Ani couldn’t comprehend a story about soccer, I concurred. Her brother played hockey and football.

In our case, all of Ani’s teachers (classroom teacher, special education teacher, occupational therapist, and speech teacher) knew her background and lack of experiences. We didn’t hide it; in fact, we shared it with the community. We wanted our neighbors to know Ani and her many talents. We also knew our family could be a strong educational advocate for inclusion, patience, and empathy.

Then and Now

As an Instructional Coach and Reading Specialist with nearly 27 years in education; I collaborate with teachers, but no longer have a classroom of my own. As I looked at Ani’s work again, I realized what I could have done better to really get to know my students and what Ani’s teachers could now do for their students.

I always asked my students to write a Dear Teacher letter at the start of the year. I recommend teachers create something similar for their students. This early communication might help a student feel comfortable right away by sharing their background..

I usually sent home to family members a Family Survey for more information. I encourage teachers to craft something like this for their students. Of course, it doesn’t have to be so in-depth; maybe five questions for each category is enough.

While I met with my students individually, we usually met to discuss their essay corrections. Now, I would structure those conferencing opportunities with more purpose and I encourage teachers to have those in-depth meetings for all student work.

I would have communicated with students’ families more often. Even though I sent emails and made phone calls, I realize now, it’s wasn’t enough. I remind teachers that I will gladly do whatever I can to give them the time to make phone calls or craft emails.

While I threw away many worksheets that day, I did not throw away Ani’s particular assignment. In fact, it is hanging in my office as a reminder of the critical importance of getting to know our students, their backgrounds and their experiences.